~ Blaise Cendrars, picaro poeta

Cendrars, un reporter, mais un reporter de Dieu ; un aventurier spirituel ; l’homme aux vingt-sept domiciles et à l’œuvre frénétique qui est notre cymbalum mundi. Cendrars, sorte de Tolstoï du transsibérien, ce huitième Oncle, a tout chanté.

(Paul Morand)

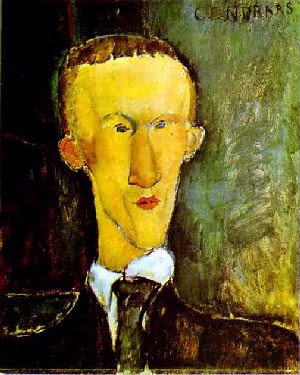

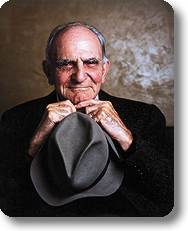

Blaise Cendrars è lo pseudonimo di Frédéric Sauser Halle. Lo psuedonimo vuole incorporare nel nome sia la fiamma - "Blaise" - che le ceneri -"Cendrars". Nato a La-Chaux-de-Fonds [Svizzera] nel 1887 (morì a Paris nel 1961), condusse una vita errabonda, viaggiando in tutti i continenti. Scrisse una serie di raccolte di versi: La leggenda di Novgorod (La légende de Novgorod, 1909), Pasqua a New York (La Pâques à New York, 1912), La prosa del transiberiano e della piccola Je hanne de France (La prose du transsibérien et de la petite Jehan ne de France, 1913). Scrisse poi numerosi romanzi, spesso di carattere autobiografico, avventuroso e esotico: L'oro (L'or, 1925), Morovagine (Morovagine, 1926), Le confessioni di Dan Yack (La confession de Dan Yack, 1929), La vita pericolosa (La vie dangereuse, 1938), La mano mozza (La main coupée, 1946), Bourlin guer (1948). Scrisse saggi. Lavorò anche nel cinema come sceneggiatore: si veda La strada (1923) diretto da Abel Gance.

Cendrars fu un tipico figlio del suo tempo, inseguì l'ideale di una letteratura capace di infrangere i vincoli della tradizione. Il suo stile in poesia è volto soprattutto all'espressione dell'irrazionale, dell'inquietudine interiore, dell'amarezza del vivere, ricco di immagini insolite e evocazioni incisive. Ebbe un notevole influsso su Apollinaire e sui surrealisti. Il suo vitalismo nomadistico e la sua costante esplorazione del mondo suggestionarono in varia misura scrittori come Valery Larbaud e Paul Morand.

BLAISE CENDRARS,

BLAISE CENDRARS,LO SCRITTORE CHE DIVISE LA STANZA

CON CHARLOT E A CUI È DEBITORE

GUILLAUME APOLLINAIRE

di Francesco Varanini

In una poesia scrive "sono il primo che porta questo nome", e precisa: "perché me lo sono inventato io di sana pianta". Si chiamava in realtà Frédéric Sauser-Hall. E la sua stessa biografia è un romanzo, in parte misteriosa, in parte inventata.

Una leggenda fa nascere il poeta a Parigi, in un albergo della rue Saint-Jacques. Ma Frédéric nasce in realtà nel 1887 a La Chaux-de-Fonds, in Svizzera, da padre svizzero e madre scozzese.

A sette anni Frédéric è in collegio a Napoli, mentre il padre compra e vende terreni al Vomero. Viaggia con la famiglia in Egitto, in Inghilterra. A quindici anni, quando la famiglia si è stabilita a Neuchâtel, prende il treno per Basilea, attraversa la Germania, segue in Russia un trafficante ebreo. Con lui viaggia Russia, in Cina, in Armenia, in India. Si rifiuta di sposare la figlia del commerciante, è denunciato, fugge in Asia Minore, sbarca a Napoli.

A vent'anni, nei sobborghi di Parigi, si occupa di apicoltura. Due anni dopo, a Bruxelles e a Londra (dove divide la camera con Charlie Chaplin), lavora come giocoliere e clown in un locale notturno. Poi in Russia, negli Stati Uniti, in Canada, a Winipeg (lavora in una trattoria), ad Anversa (lavora in una società di navigazione), poi di nuovo a New York.

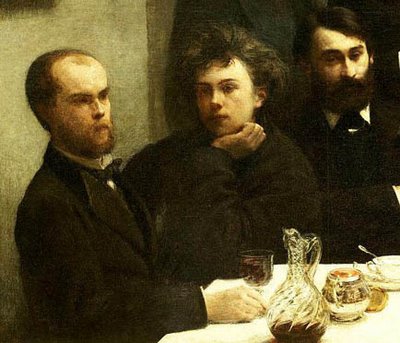

Tornato a Parigi, pubblica a sue spese Pasqua a New York. Siamo nel 1912: nello studio del pittore Delaunay si fa salotto, il giovane, eccentrico viaggiatore è sollecitato a recitare i propri versi. Tra i presenti Apollinaire, che ascolta in silenzio, ad occhi chiusi. L'anno dopo Apollinaire pubblicherà Alcools, salutato come esordio della poesia d'avanguardia. Ma il debito nei confronti di Cendrars è grande.

Due anni dopo, Sauser è volontario nella Legione Straniera. Gravemente ferito da una scheggia di granata, subisce l'amputazione del braccio destro. E per reazione prende a praticare gli sport più violenti e pericolosi, dalla boxe all'automobilismo. Studia inoltre stenografia e rifiuta l'arto artificiale.

Con un gruppo di zingari, conduce vita nomade nelle campagne francesi. Si ritira in una fattoria abbandonata. Fonda una casa editrice. Si occupa di cinema, a Roma. Nel 1924 si imbarca per il Brasile; l'anno dopo torna in Francia e in un mese scrive L'oro. Termina Moravagine, storia romanzata dei suoi anni giovanili. Tra il 1925 e il 1929 viaggia lungamente nell'America del Sud. Si dedica al giornalismo, corrispondenze di viaggio e poi, con la seconda guerra mondiale, dal fronte. Dopo la rottura del fronte, lunga peregrinazione per le strade di Francia sulla sua Alfa Romeo disegnata da Braque.

Una serie di interviste radiofoniche, nel 1952, lo rendono finalmente noto. Nel 1956, colpito da paralisi, è costretto all'immobilità. Nel 1959 riceve la Legion d'Onore; nel 1961 il Gran Premio Letterario Città di Parigi. Lo ritira la seconda moglie, famosa attrice. Quattro giorni dopo Cendrars muore.

ILES

Iles

Iles

Iles

Iles où l’on ne prendra jamais terre

Iles où l’on ne descendra jamais

Iles couvertes de végétations

Iles tapies comme des jaguars

Iles muettes

Iles immobiles

Iles inoubliables et sans nom

Je lance mes chaussures par-dessus bord car je voudrais bien aller jusqu’à vous

TU ES PLUS BELLE QUE LE CIEL ET LA MER

Quando ami devi partire

Lascia tua moglie lascia tuo figlio

Lascia il tuo amico lascia la tua amica

Lascia la tua amante lascia il tuo amante

Quando ami devi partire

~ * ~

Quand tu aimes il faut partir

Quitte ta femme quitte ton enfant

Quitte ton ami quitte ton amie

Quitte ton amante quitte ton amant

Quand tu aimes il faut partir

Le monde est plein de nègres et de négresses

Des femmes des hommes des hommes des femmes

Regarde les beaux magasins

Ce fiacre cet homme cette femme ce fiacre

Et toutes les belles marchandises

II y a l'air il y a le vent

Les montagnes l'eau le ciel la terre

Les enfants les animaux

Les plantes et le charbon de terre

Apprends à vendre à acheter à revendre

Donne prends donne prends

Quand tu aimes il faut savoir

Chanter courir manger boire

Siffler

Et apprendre à travailler

Quand tu aimes il faut partir

Ne larmoie pas en souriant

Ne te niche pas entre deux seins

Respire marche pars va-t'en

Je prends mon bain et je regarde

Je vois la bouche que je connais

La main la jambe l'œil

Je prends mon bain et je regarde

Le monde entier est toujours là

La vie pleine de choses surprenantes

Je sors de la pharmacie

Je descends juste de la bascule

Je pèse mes 80 kilos

Je t'aime

=> Extrait "Du Monde entier, Au Coeur du Monde":

Tu m'as dit si tu m'écris

Ne tape pas tout à la machine

Ajoute une ligne de ta main

Un mot un rien oh pas grand chose

Oui oui oui oui oui oui oui oui

Ma Remington est belle pourtant

Je l'aime beaucoup et travaille bien

Mon écriture est nette est claire

On voit très bien que c'est moi

qui l'ai tapée

Il y a des blancs que je suis seul à savoir faire

Vois donc l'oeil qu'à ma page

Pourtant, pour te faire plaisir j'ajoute à l'encre

Deux trois mots

Et une grosse tache d'encre

Pour que tu ne puisses pas les lire.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

| CONTRASTES Les fenêtres de ma poésie sont grand'ouvertes sur les boulevards et dans ses vitrines Brillent Les pierreries de la lumière Écoute les violons des limousines et les xylophones des linotypes Le pocheur se lave dans l'essuie-main du ciel Tout est taches de couleur Et les chapeaux des femmes qui passent sont des comètes dans l'incendie du soir | CONTRASTS The windows of my poetry are wide open to the boulevards and in the showcases Shine The precious stones of light Listen to the violins of the limousines and the xylophones of the linotypes The painter washes himself in the hand towel of the sky Everything is splashes of colour And the hats of the passing women are comets in the fire of the evening |

CONTRASTI

Le finestre della mia poesia sono spalancate sui

Boulevards e nelle vetrine

Brillano

Le gemme di luce

Ascolta i violini delle limousines e gli xilofoni

Dei linotipi

Il pittore si lava con l’asciugamano del cielo

È tutto un getto di colore

E i cappelli delle donne che passano sono comete

Nell’incendio della sera

=> Estratto da / extrait / excerpted from (check the bold section in the full English translation below):

LA PROSE DU TRANSSIBERIEN ET LA PETITE JEHANNE DE FRANCE

En ce temps-la, j'etais en mon adolescence

J'avais a peine seize ans et je ne me souvenais deja plus de mon enfance

J'etais a 16.000 lieues du lieu de ma naissance

J'etais a Moscou dans la ville des mille et trois clochers et des sept gares

Et je n'avais pas assez des sept gares et des mille et trois tours

Car mon adolescence etait si ardente et si folle

Que mon coeur tour a tour brulait comme le temple d'Ephese ou comme la Place Rouge de Moscou quand le soleil se couche.

Et mes yeux eclairaient des voies anciennes.

Et j'etais deja si mauvais poete

Que je ne savais pas aller jusqu'au bout.

Le Kremlin etait comme un immense gateau tartare croustille d'or,

Avec les grandes amandes des cathedrales, toutes blanches

Et l'or mielleux des cloches...

Un vieux moine me lisait la legende de Novgorode

J'avais soif

Et je dechiffrais des caracteres cuneiformes

Puis, tout a coup, les pigeons du Saint-Esprit s'envolaient sur la place

Et mes mains s'envolaient aussi avec des bruissements d'albatros

Et ceci, c'etait les dernieres reminiscences

Du dernier jour

Du tout dernier voyage

Et de la mer.

[…]

~ Qualcosa in inglese / English pieces:

The greatest poet of the Cubist epoch was Pierre Reverdy, because he had distinguished emotions. The next was Gertrude Stein, because she had none. Both had perfect ears and impeccable style. Blaise Cendrars (1887-1961), like Max Jacob, was a professional personality of the same period, rather than an artist. Henry Miller wrote about Cendrars extensively and admired him greatly. They have a good deal in common.

Both Cendrars and Miller present themselves to the public as livers rather than artists, and both have a talent for engaging implausibility, which sometimes catches them short. Actually this sort of thing is just as literary as Walter Pater or Henry James. It’s just a different pitch, and it depends for its effectiveness on its literary convincingness. Blaise Cendrars portrays himself in his poetry as a more picaresque and more robust and very French Whitman, a nonchalant knockabout who had been for to see and for to admire in all the most remote and exciting parts of the world.

It is interesting to go back and read some of the things that made his reputation — the volume called Kodak, the poem “Far West,” most emphatically pronounced “Fahvest,” as you discover on reading it. San Bernardino, California, is built in the center of a verdant valley, watered by a multitude of little brooks from the neighboring mountains. Trout pullulate in these brooks; innumerable herds graze in the fat fields and the shepherd stuff themselves with the local fruits, which include pineapples. Game abounds. The lapin à queue de coton called “cottontail” and the hare with long ears called “jackass,” the chat sauvage and le serpent à sonnette, “rattlesnake,” but there aren’t any more pumas nowadays. So it goes on. Hilaire Hiler used to read this whole poem, ad-libbing all sorts of French-pronounced Westernisms with hilarious effect on the select audience in the old Jockey on Boulevard Montparnasse.

As a cowboy poet, Cendrars is, I’m afraid, only a cooey-booey. As a poet of tourism, he is less convincing than Valéry Larbaud and his world-wandering, world-weary billionaire, A.O. Barnabooth. Yet convincing he is, not for what he pretends to be, but for what he is. He is the poet of the lumpen demimonde, of the sword-swallowers, escape-artists and streetcorner acrobats in the cheap hotels back of the Gaïté, of the worn and innocent whores of the Passage du Départ with runs in their stockings and holes in their shoes. It’s not just that he writes about them, although when he does he’s very good indeed, but that he thinks like them and speaks in their very voices.

This is not true of other poets of the métier, who sublimate the idiom with their own sentiment. This is the sort of thing that translators seem unable to catch. The desperate insouciance that underlies the rhythms of Cendrars’s verse and the twists of his syntax are inaccessible to American professors of French who get foundation grants.

Yet Cendrars was also intellectual and the introduction to these translations makes much of his writing on poetics. His ideas are pretty much the orthodoxy of the Cubist period and now have the musty smell of dead café conversation. Our principal emotion on reading Cendrars today is nostalgia for him and his friends and the beautiful epoch in which they came to maturity, and this is greatly reinforced by the fact that nostalgia is also close to being his own principal subject. Far away at the ends of the earth he meets a wandering tart on a transcontinental train and all the sordid purgatorial excitement of the streets of Paris lit with prostitutes floods back on him. The Far West or the Argentine pampas, which he probably never saw, are symbols of lost innocence and glamour.

One of Cendrars’s most important contributions to French literature is his prosody. He began writing vers libre in Vielé-Griffin’s sense, which is not to be translated “free verse,” but which in Cendrars’s case was a kind of rushing, sprung alexandrine or hexameter or hendecasyllable. In his first long poem this approaches the impetuous rocking rhythm of Apollinaire’s “Zone.” Cendrars, although he always denied discipleship, was a very obvious continuator of one aspect of Apollinaire, as person, poet and prosodist. Soon he was writing free verse in the English sense, a little like the early, best poetry of Carl Sandburg or even more like the long swaying rhythms of Robinson Jeffers.

His translators do not manage to transmit these virtues. I think the reason is that poetry like Cendrars’s, for all its surface blustery extroversion, is really very intimate. To translate him successfully, it would be necessary to have either shared his background and his attitude toward it or to be a consummate actor able to project oneself imaginatively into almost complete identification with his personality. However, this book contains the French texts on facing pages, and the English is usually not too far off to serve as a pony.

The youngest generation of American poets should find Cendrars stimulating. It’s a long time since poetry like this, as good as this, has been written in America. Nothing less like the imitation Jacobean verse of the older Establishment and the Pound-Williams-Olson verse of the new Establishment could be imagined. People are trying to write like this again and Cendrars could be of help — although the world of the working-class Bohemia of the slums of Paris that gives his poetry its special quality is utterly vanished from the earth.

INTRODUCTION TO THE TRANS-SIBERIAN OF BLAISE CENDRAR

(Introduction and translation by Ekaterina Likhtik)

Blaise Cendrars is one of the first to introduce modernity into twentieth century poetry. With his style he ushers in a spirit of innovation into writing, he works diligently and tirelessly to find a way to express himself, a way to write his life. In 1910 he writes to his friend Fela in New York, “Ten years of study. I need ten years and I will find my own language. My style.” He spends about a year in New York between 1911 and 1912, deliriously hungry most of the time, but letting nothing deter him from his goal: he must develop his style. For him to write is not a Romantic notion, it is the exhaustive “work of a artisan.” In 1911 he changes his given name, Frédéric-Louis Sauser, to Blaise Cendrars, incorporating into his identity the words “Blaze” and “Ashes”.

For Cendars Trans-Siberian is the transition to a self-defined and elaborated poetic style. He solidifies that style, emphasizing the key to his poetry in the title. Stylistically it is “prose” on which he insists in his poetry. Cendrars is first inspired by the idea of “prose” in the work of Remy de Gourmont in his Le Latin Mystique. In it he discovers the hymns and free verse of the medireview monks of Saint-Gall. Cendrars finds Le Latin Mystique a profoundly humane work, and searches for a way to appeal to the populace at large with his writing, seeking to reverberate in as many layers of the reading public as possible. He says, “I used the word 'prose' in the Trans-Siberian in the early Latin sense of prosa dictu. Poem seemed to me too pretentious, too narrow. Prose is more open, popular.” Blaise attempts to cross the social bridges that often surround poetry, and in that sense his attitude is proletarian. His vocabulary is often offensive to the contemporary aristocracy and his versification is deemed unorthodox.

Cendrars is full of vigor and initiative. He constantly travels, he writes, and, after becoming better known and recognized for his poetic genius, he starts up magazines, he is an art critic, he publishes unknown authors, he explores the spaces between the obvious, he wants to get to the bottom of suffering. The Trans-Siberian describes his initiation or crossing over into manhood, both sexually and spiritually. This is his first great voyage, of which he was able to write for the first time “I saw” in the same way that Goya has written “Yo lo vi”.

Having lived in St. Petersburg, in New York, in London, in Switzerland, having visited an enormously large part of the world and fought in World War I, he is one of the more cosmopolitan poets of the time. This knowledge of the world, of literature, of war and of international lore can all be seen in the Trans-Siberian. The violence of the poem as well as the many references to war and death are associated with the Russo-Japanese war (1904-1905), and the Russian Revolution of 1905, two events that Cendrars witnessed while in Russia. The work of Cendrars resonates with as much force now at the other end of the twentieth century, as it did in his time. It builds a bridge for us to cross from the beginning of the 20th to the beginning of the 21st.

TRANS-SIBERIAN PROSE AND LITTLE JEANNE FROM FRANCE

I was in my adolescence at the time

Scarcely sixteen and already I no longer remembered my childhood

I was 16,000 leagues from my birthplace

I was in Moscow, in the city of a thousand and three belfries and seven railroad stations

And they weren't enough for me, the seven railroad stations and the thousand and three towers

For my adolescence was so blazing and so mad

That my heart burned in turns as the temple of Epheseus, or as Red Square in Moscow

When the sun sinks.

And my eyes shone upon the ancient routes

And I was already such a bad poet

That I didn't know how to go all the way to the end.

The Kremlin was like an immense Tatar cake

Crusted with gold,

With great almonds of cathedrals all done in white

And the honeyed gold of the bells…

An old monk was reading to me the legend of Novgorod

I was thirsty

And I was deciphering cuneiform characters

Then, suddenly, the pigeons of the Holy Spirit soared above the square

And my hands also flew up, with the rustling of the albatross

And these, these were the last recollections of the last day

Of the entire last voyage

And of the sea.

But I was a very bad poet.

I didn't know how to go to all the way to the end.

I was hungry

And all the days and all the women in the cafés and all the glasses

I would have liked to drink and to break them

And all the shop windows and all the streets

And all the homes and all the lives

And all the wheels of the hackney cabs turning in a whirlwind on the bad cobblestones

I would have wanted to thrust them into a furnace of swords

And I would have wanted to crush all the bones

And to tear out all the tongues

And to liquefy all the big bodies strange and naked under the clothing that drives me to madness…

I sensed the coming of the great red Christ of the Russian revolution…

And the sun was a bad wound

That split open like a burnt up inferno.

I was in my adolescence at the time

I was scarcely sixteen and already I didn't remember my birth

I was in Moscow, where I wanted to feed on flames

And they weren't enough for me the towers and the railroad stations that studded my eyes like constellations

In Siberia the cannon roared, it was war

Hunger cold plague cholera

And the muddy waters of Love pulled along millions of carrion

In all the railroad stations I saw departing all the last trains

No one could leave any more for the tickets were no longer sold

And the soldiers who were going away would have very much liked to stay…

An old monk sang to me the legend of Novgorod.

Me, the bad poet who didn't want to go anywhere, I could go everywhere

And also the merchants still had enough money

To go and tempt fate.

Their train left every Friday morning.

It was said there were a lot of deaths.

One merchant carried away one hundred crates of alarm clocks and cuckoos from the Black Forest

Another, hatboxes, top hats and an assortment of Sheffield corkscrews

Another, coffins from Malmoi filled with canned food and sardines in oil

Then there were lots of women

Women renting between their legs and who could also serve

Coffins

They were all patented

It was said there were a lot of deaths over there

They traveled at reduced prices

And had an open account at the bank.

Now, one Friday morning, it was finally my turn

It was December

And I too left to accompany a salesman in the jewelry business traveling to Kharbin

We had two coupés in the express and 34 chests of jewelry from Pforzheim

From the German peddler “Made in Germany”

He had dressed me in new clothes, and while boarding the train I lost a button

—I remember it, I remember it, I have often thought of it since—

I was sleeping on the trunks and I was very happy to play with the nickel-plated browning

that he had also given me

I was very happy carefree

I made believe we were robbers

We had stolen the treasure of Gloconde

And were going, thanks to the Trans-Siberian, to hide it on the other side of the world

I had to defend it against bandits from Ural who had attacked Jules Vern's traveling acrobats

Against the Khoungouzes, the Chinese boxers

And the Great Lama's enraged little Mongols

Ali Baba and the forty thieves

And those faithful to the terrible Old Man of the Mountain

And especially, against the most modern of all

The hotel rats

And all the specialists from international express trains everywhere.

And yet, and yet,

I was as sad as a child

The rhythms of the train

The “railway marrow” of American psychiatrists

The noise of the doors the voices the axles screeching on the frozen rails

The golden railing of my future

My browning the piano and the cursing of the card players in the next-door compartment

The splendid presence of Jeanne

The man in the blue glasses who nervously paced the hallway and who would look at me as he passed by

Rustling of women

And whistling of steam

And the eternal sound of wheels whirling in madness in the furrows of the sky

The windows frosted over

No nature!

And behind, the Siberian plains the low sky and the great shadows of the Taciturn Ones rising and falling

I am asleep in a blanket

Checkered

As is my life

And my life keeps me no warmer than this Scottish shawl

And all of Europe glimpsed in gusts of wind from a full steam express

Is no richer than my life

My poor life

This shawl

Unraveled on the trunks that are filled with gold

With which I trundle forth

And I dream

And I smoke

And the only flame in the universe

Is one poor thought…

From the depth of my heart tears rise

If I think, Love, about my mistress;

She is but a child, whom I found so

Pale, immaculate, in the back rooms of a bordello.

She is but a child, blond, blithe and sad,

She doesn't smile and never cries;

But deep in her eyes, when she lets you drink from them,

There trembles a gentle silver lily, the poet's flower.

She is meek and silent, and without reproach,

With a drawn out shiver at your approach;

But when I come to her, from here, from there, from a party,

She takes a step, then closes her eyes – and takes a step.

For she is my love, and the other women

Have nothing but golden dresses on great bodies ablaze,

My poor companion is so lonesome,

She is completely nude, she has no body – she is too poor.

She is but a candid, frail flower,

The poet's flower, a slight silver lily,

So cold, so alone, and already so wilted

That tears well up in me if I think of her heart.

And this night is like one hundred thousand others when a train presses on in the night

— The comets fall —

And a man and a woman, even when young, muse in making love.

The sky is like the shredded tent of a poor circus in a small fishing village

In Flanders

The sun is a smoky oil lamp

And at the very top of a trapeze a woman makes a moon.

The clarinet the piston a sharp flute and a bad tambourine

And here is my cradle

My cradle

It was always next to the piano when my mother like Madame Bovary played Beethoven sonatas

I spent my childhood in the Hanging Gardens of Babylon

And skipping school, in the railroad stations in front of departing trains

Now, I have made all the trains run behind me

Basel-Timbuktu

I have also bet on the races at Auteuil and at Longchamp

Paris – New York

Now, I have made all the trains run the course of my life

Madrid – Stockholm

And I lost all my bets

There is now only Patagonia, Patagonia, that suits my immense sadness, Patagonia, and a journey to the South Seas

I'm on the road

I've always been on the road

I'm on the road with little Jehanne from France

The train makes a perilous jump and falls back on all of its wheels

The train falls back on its wheels

The train always falls back on all of its wheels

“Blaise, tell me, are we very far from Montmartre?”

We are far, Jeanne, you've been on the move for seven days

You are far from Montmartre, from the Hill that nourished you from Sacre-Cœur that cradled you

Paris has disappeared and its enormous flame

There is nothing but continuous ash

Falling rain

Rising peat

Whirling Siberia

Heavy rebounding sheets of snow

And the bell of madness that quivers like the very last wish in the bluish air

The train beats at the heart of the heavy horizons

And your sorrow sneers…

“Tell me, Blaise, are we very far from Montmartre?”

The worries

Forget the worries

All the railroad stations cracked askew on the road

The telegraph wires on which they hang

The grimacing lampposts gesticulate and strangle them

The world expands elongates and retracts like an accordion tormented by a sadistic hand

In the shreds of the sky, locomotives in a fury

Flee

And in the holes,

The dizzying wheels the mouths the voices

And the dogs of misfortune that bark at our parcels

The demons are unchained

Scrap iron

All is in false harmony

The broom-room-room of the wheels

Jolts

Bouncing back

We are a storm in the skull of the deaf…

“Tell me, Blaise, are we very far from Montmartre?”

You irritate me, of course you know very well, we are far

Overheated madness bellows in the locomotive

The plague cholera arise on our road like burning embers

We disappear in the war completely in a tunnel

Hunger, the whore, clings to the clouds as it spreads

And battle droppings are in rancid heaps of corpses

Do as she does, perform your craft…

“Tell me, Blaise, are we very far from Montmartre?”

Yes, so we are, so we are

All the scapegoats have croaked in this desert

Hear the screech of this mite-infested herd Tomsk

Cheliabinsk Kainsk Ob Tai Shan Verkneudinsk Kurgan Samara Pensa-Tulun

Death in Manchuria

Is our last stop our last lair

This voyage is terrible

Yesterday morning

Ivan Ulitch had white hair

And Kolya Nikolai Ivanovich has been gnawing his fingers for fifteen days now…

Do as she does Death Hunger perform your craft

It costs one hundred sou, in the Trans-Siberian, it costs one hundred rubles

The benches in fever and red flashes under the table

The devil is at the piano

His gnarled fingers arouse all the women

Nature

Whores

Perform your craft

Until Kharbin…

“Tell me, Blaise, are we very far from Montmartre?”

No but…get the hell out…leave me alone

You have angular hips

Your stomach is sour and you have the clap

That's all that Paris has put in your bosom

There's also a bit of soul… because you are unhappy

Feel my pity feel my pity come towards me unto my heart

The wheels are windmills from the land of Cocagne

The windmills are crutches twirled by a beggar

We are the cripples of emptiness

We roll on our four sores

Our wings have been clipped

The wings of our seven sins

And all the trains are paddleballs of the devil

Farmyard

The modern world

Speed can't do much here but

The modern world

The faraway places are just too far

And at the end of the journey it's terrible to be a man with a woman…

“Blaise, tell me, are we very far from Montmartre?”

Feel my pity feel my pity come towards me I will tell you a story

Come to bed

Come unto my heart

I'm going to tell you a story…

Oh come! come!

In Figi spring reigns eternal

Laziness

Love swoons couples in the tall grass and hot syphilis lurks under banana trees

Come to the lost isles of the Pacific!

They are called Phoenix the Marquesas

Borneo and Java

And Sulaweisi in the form of a cat.

We can not go to Japan

Come to Mexico!

On its high plateaus tulips bloom

Tentacular creepers are the hair of the sun

Could almost be the palette and brushes of a painter

Colors deafening as gongs

Rousseau went there

There he bedazzled his life

It is the country of birds

The bird of paradise, the lyrebird

The toucan, the mocking bird

And the colibri nest among the black lilies

Come!

We will love one another in the majestic ruins of Aztec temples

You will be my idol

A checkered childish idol a little ugly and grotesquely odd

Oh come!

If you wish we will go by plane and we will fly over the country of a thousand lakes,

The nights there are immeasurably long

A prehistoric ancestor will be afraid of my motor

I will land

And I will construct a hangar for my plane with the fossils of mammoths

A primitive fire will reheat our paltry love

Samovar

And we will love one another conventionally near the pole

Oh come!

Jeanne Jeannette Pipette nono niplo nipplette

Mimi milove my dovedew my Peru

Sleepy me zeezee

Moor my manure

Dear li'l-heart

Tart

Beloved li'l goat

My li'l-sin sweet

Halfwit

Halloo

She sleeps.

She sleeps

And of all the hours of the world she hasn't swallowed a single one

All faces glimpsed in railroad stations

All clocks

The time in Paris the time in Berlin the time in Saint Petersburg and the time in all stations

And in Ufa, the blood stained face of the cannoneer

And the foolishly glowing dial in Grodno

And the perpetual rushing of the train

Each morning we set our watches to the hour

The train advances and the sun retreats

Nothing to be done, I hear the echoing bells

The great bell of Notre-Dame

The shrill bell of the Louvre that tolled Bartholomew's

The rusted peal of bells on the death of Bruge-la-Morte

The electric rings of the library bells in New York

The Venice countryside

And the bells of Moscow, the clock of the Red Door that counted for me my hours in an office

And my memories

The train weighs on the revolving plates

The train rolls

A grasseye gramophone a gypsy march

And the world, like the Jewish quarter clock in Prague deliriously turns backwards.

Strip the rose of the winds

Here murmur unchained storms

Trains roll on in a flurry on entangled tracks

Diabolical paddleballs

There are trains that never meet

Others lose themselves on the way

Stationmasters play chess

Backgammon

Billiards

Pool balls

Parables

The steel-rimmed track is a new geometry

Syracuse

Archimedes

And the soldiers who slit his throat

And the galleys

And the vessels

And the prodigious engines he invented

And all the slaughter

Ancient history

Modern history

The whirlwinds

The shipwrecks

Even the Titanic, I read it in a magazine

So numerous the visual associations that I can't develop them all in my verses

For I am still a very bad poet

For the universe overwhelms me

For I have neglected to insure myself against railroad accidents

For I don't know how to go all the way to the end

And I'm afraid

I'm afraid

I don't know how to go all the way to the end

Like my friend Chagall I could make a series of insane drawings

But I haven't taken notes on my way

“Forgive me my ignorance

“Forgive me for no longer knowing the age-old game of poetry”

As Guillaume Appollinaire says

One can read everything about war

In the Kuropatkin Memoirs

Or in the Japanese journals that are just as brutally illustrated

To what end document myself?

I abandon myself

To bursts of memory…

From Irkutsk on the voyage became much too slow

Much too long

We were in the first train to circle lake Baikal

We had adorned the train with flags and Chinese lanterns

And we left the station to sad strains of the hymn to the Tsar.

If I were a painter I would pour a lot of red, a lot of yellow on the end of this voyage

For I believe that we were all a little mad

And that an immense fever bloodied the worked-up faces of my companions on this journey

As we approached Mongolia

That roared like a fire.

The train had slowed its pace

And I noticed in the perpetual grating of the wheels

The mad accents and the sobbing

Of an eternal liturgy

I saw

I saw silent trains black trains returning from the Orient passing like phantoms

And my eye, as a headlight, still runs after these trains

In Talga 100,000 wounded were agonizing for lack of care

I visited the hospitals of Krasnoyarsk

And in Khilok we came across a long convoy of soldiers gone mad

I saw in the lazarettos the gaping gashes wounds that bled to the bone

And amputated limbs danced around or soared through the raucous air

Fire was on all faces in all hearts

Idiotic fingers were rapping on all windowpanes

And under the force of fear the stares burst open like abscesses

In all the stations all the wagons burned

And I saw

I saw trains with 60 engines escaping at full steam hounded by horizons in heat and flocks of crows that afterwards took hopeless flight

Disappearing

In the direction of Port Arthur.

In Chita we had a few days of rest

A five-day stop since the tracks were blocked

We spent it with Mister Yankelivitch who wanted to give me his only daughter in marriage

Then the train took off.

Now it was I who took a seat at the piano and I had a toothache

When I wish to I can still recall that interior the father's store and the daughter's eyes who in the evenings came to my bed

Mussogorsky

And the lieder of Hugo Wolf

And the Gobi sands

And in Khailar a caravan of white camels

I am sure I was drunk for more than 500 kilometers

But I was at the piano and that's all I could see

When you travel, you should close your eyes

Sleep

I would have liked so much to sleep

I recognize all the countries with my eyes closed by their odor

And I recognize all the trains by their rumbling

European trains have four beats while those in Asia are at five or seven beats

Others move softly and these are lullabies

And there are those that in the monotonous noise of their wheels remind me of Maeterlinck's heavy prose

I've deciphered all the wheels' chaotic texts and I've assembled the disparate elements of a violent beauty

That I possess

And which compels me.

Tsitsihar and Kharbin

I am not going any further

It is the last station

I got off at Kharbin as they had just set fire to the Red-Cross office.

O Paris

Large glowing hearth with the crossed pokers of your streets and your old homes that hunch over warming themselves

Like forefathers

And here are the posters, red and green multicolored as my brief yellow past

Yellow the proud color of French novels sold abroad.

I love to squeeze into moving buses in big cities

Those of the Saint-Germain-Montmartre line bring me to the assault of the Hill

The motors bellow like golden bulls

The bovine twilight grazes the Sacre Cœur

O Paris

Central station last stop of desire crossroads of unrest

Only the merchants of color still have a little bit of light on their doors

The “International Company of Sleeping Cars and Europeans Express Trains” has sent me their brochure

It is the most beautiful church in the world

I have friends who surround me like guardrails

They are afraid that when I leave I won't return

All the women I have met tower on the horizons

With gestures full of pity and the sad look of traffic lights in the rain

Bella, Agnes, Catherine, and the mother of my son in Italy

And the one, the mother of my love in America

There are siren screams that rip my soul

There in Manchuria a stomach still throbs as if in labor

I would like

I would like to have never gone traveling

This evening a great love torments me

And despite myself I think of little Jehanne from France.

It is on an evening of sadness that I wrote this poem in her honor.

Jeanne

The little prostitute

I am sad I am sad

I will go to the Lapin Agile to again remember my lost youth

And drink a few glasses

Then I will return alone

Paris

City of the inimitable Tower, the great Gallows and the Wheel.

Paris, 1913

~ Some more biographical notes:

Blaise Cendrars wrote in French and spent much of his life travelling restlessly. He did his best to fictionalize his past and his biographers have had much difficulties separating fact from fabulations. Cendrars's most famous novels, Sutter's Gold and Moravagine, both from 1926, have been translated into more than twenty languages. In his novels, featuring resilient heroes, Cendrars used often his cosmopolitan wanderings as a way to discover inner truths.

I straighten my papers I set up a schedule My days will be busy I don't have a minute to lose I write (from Complete Poems, 1992, tr. Ron Padgett) | Raddrizzo le mie carte Preparo un programma I miei giorni saranno indaffarati Non ho un minuto da perdere Scrivo (trad. Daubmir) |

Blaise Cendrars was born in the small city of La Chaux-de-Fonds of a Swiss father and a Scottish mother. He was educated in Neuchâtel, and later in Basle and Berne. At the age of 15 he ran way home - according to a story he escaped from his parents but another version tells his family gave up keeping him in school. Cendrars worked in Russia as an apprentice watchmaker and was there during the Revolution of 1905. In 1907 he entered the university of Berne but settled in 1910 in Paris, adopting French citizenship.

During his life Cendrars worked worked at a variety of jobs - as a film maker, journalist, art critic, and businessman. Before becoming writer he even tried horticulture and never stopped trying to earn his living by extra-literary activities. In World Authors 1900-1950 (ed. by Martin Seymour-Smith and Andrew C. Kimmens, 1996) Cendrars wrote that in his youth he traveled widely in China, Mongolia, Siberia, Persia, the Caucasus and Russia, and later in the Unites States, Canada, South America, and Africa. Some doubts have arisen whether he stoked trains in China in his youth, but perhaps this is more important from the biographical point of view than literary - the memoirs of Marco Polo, Cellini and Casanova and the autobiographical novels of Jean Genet and Henri Charrière are read in spite of reliability in all biographical details. Like the protagonist of Les confessions de Dan Yack (1928), Cendrars was a man of action, who avoided "literary" flavor in his prose, and a man of contemplation, who had almost obsessive need for exotic experiences. In Easter in New York (1912) he wrote: "Still, Lord, I took a dangerous voyage / To see a beryl intaglio of your image. / Lord, make my face, buried in my hands, / Leave there its agonizing mask."

Cendrars was considered along with Apollinaire, whom he deeply influenced, a leading figure in the literary avant-garde before and after World War I. In his early experimental poems Cendrars used pieces of newsprint, the multiple focus, simultaneous impressions, and other modernist techniques. La prose du Transibérien et de la petite Jeanne de France (1913), a combination of travelogue and lament, was printed on two-meter pages with parallel abstract paintings by Sonia Delaunay. Le Panama ou les aventures de mes sept oncles (1918) was in the form of a pocket timetable. Cendrars was closely associated with Cubism but he also published poetry Jacques Vache's Lettres de guerre, which was edited by Philippe Soupault, André Breton and Louis Aragon - founders of surrealism in literature.

Prose of the Transsiberian contains impressions from Cendrars's real or imaginary journey from Moscow to Manchuria during the 1905 Revolution and Sino-Russian War. As the train of the title speeds through the vast country, Cendrars mixes with its movement images of war, apocalyptic visions of disaster, and fates of people wounded by the great events.

Cendrars traveled incessantly and after 1914 became involved in the movie industry in Italy, France, and the United States. During World War I Cendrars joined the army. He served as a corporal and lost in 1915 in combat his right arm. In 1924 Cendrars met in Paris the American writers John Dos Passos and Hemingway. Ten years later he became friends with Henry Miller; their correspondence was published in 1995 in English. During a two-week stay in 1936 in Hollywood he wrote his impressions for Paris-Soir in series of articles which were collected in Hollywood, la mecque du cinéma (1936). It depicts with wry humour the movie industry and the town's people. Films were one of Cendrars's passions - he had worked as early as in 1918 with the director Abel Gance.

By 1925 Cendrars had ceased to publish poetry. Among his famous prose works in the 1920s is L'or (Sutter's Gold), a fictionalized story of John Sutter, a Swiss pioneer, who started the great gold rush in the northern California, built there his own empire but died in poverty. According to a literary anecdote, Stalin kept this book on his night table. Sutter's Gold can be read as the author's exploration of his inner self, like the semi-autobiographical novel Moravagine ('Death to the vagina'). In it Cendrars followed a madman, a descendant of the last King of Hungary, and a young doctor on their worldwide adventures from the Russian Revolution and to the First World War. Moravagine's madness becomes comparable with the dissolution of world and the chaotic disorder of life. "There is no truth. There's only action, action obeying a million different impulses, ephemeral action, action subjected to every possible imaginable contingency and contradiction. Life." Moravagine dies in an another asylum and the manuscript of the story finds it way to Cendrars, one of the characters in it.

The Russian filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein tried to arose Hollywood's interest in Sutter's Gold on his trip there in the 1930s. The director William Wyler obtained a scenario that Eisenstein had prepared and read plays based on the life of Sutter, including Bruno Frank's The General and the Gold and Caesar von Arx's John Augustus Sutter. Cendrars offered Wyler his services as a screenwriter, and hopefully wrote: "Should this film be succesful, I have several other first-class American scenarios." After Universal engaged William Anthony McGuire, Cendrars offered to read the script "absolutely gratis." However, Wyler was pulled off the project and Howard Hawks was assigned to it. Eventually James Cruze directed the film version, which was released in 1936. It was one of the studio's major flops of the year, and started the exit of Carl Laemmle from the chairman's office. Most of the action footage of the film was reused in Mutiny on the Blackhawk (1939).

During the German occupation of France from 1940 to 1944 Cendrars was listed as a Jewish writer of "French expression". His younger son was killed in an accident while escorting American planes in Morocco. He also had a daughter, Miriam, who later published a biography (Blaise Cendrars, 1985). Cendrars started to publish in the late 1940s memoirs, which combined travel fantasies with colorful episodes from his life. In L'homme foudroyé (1945, The Astonished Man) Cendrars walks around between lines of World War I trenches, spends time with gypsies in a travelling theatre, and attempts to drive across a South American swamp. "I am haunted by no phantoms. It is rather that the ashes I stir up contain the crystallization that hold the image (reduced or synthetic) of the living and impure beings that they constituted before the intervention of the fire. If life has a meaning, this image (from the beyond?) has perhaps some significance. That is what I should like to know. And it is why I write."- Cendrars received in 1961 the Paris Grand Prix for literature, a recognition which almost came too late. Blaise Cendrars died a few days later on January 21, 1961, in Paris.

SELECTED WORKS:

• La légende de Novgorode, 1909?

• Les Pâques à New York, 1912 - Easter in New York

• La prose du Transibérien et de la petite Jeanne de France, 1913 - Prose of the Transsiberian and of Little Jeanne of France

• Séquence, 1913

• La Guerre aux Luxembourg, 1916

• Profond aujourd'hui, 1917

• J'ai Tué, 1918

• Le Panama ou les aventures de mes sept oncles, 1918 - Panama; or, The Adventures of My Seven Uncles

• La fin du monde filmée par l'Ange Notre-Dame, 1919

• Poèmes élastiques, 1919

• Du monde entier, 1919

• J'ai saigné, 1920

• Anthologie nègre, 1921- African Saga

• Feuilles de route, 1924

• Kodak (Documentaire), 1924

• L'Or, 1925 - Sutter's Gold / Gold - suom. Kulta - film 1936, dir. by James Cruze, starring Edward Arnold, Lee Tracy, Binnie Barnes

• Moravagine, 1926 - trans.

• L'eloge de la vie dangereuse, 1926

• L'eubage, 1926

• L'ABC du cinéma, 1926

• Petits Contes nègres pour les enfants des Blancs, 1928 - Little Black Stories for Little White Children

• Le Plan de l'Aiguille, 1929 - Antarctic Fugue

• Les Confessions de Dan Yack, 1929

• Une Nuit dans la forêt, 1929

• Comment les blancs sont d'anciens noirs, 1930

• Rhum, 1930 - suom. Rommi

• Aujourd'hui, 1931

• Vol à voile, 1932

• Panorama de la pègre, 1935

• Hollywood, la mecque du cinéma, 1936 - Hollywood: Mecca of the Movies

• Histoires vraies, 1937

• La vie dangereuse, 1938

• D'outremer à indigo, 1940

• Chez l'armée anglaise, 1940

• Poésies complètes, 1944

• L 'Homme foudroyé, 1945 - The Astonished Man

• La main coupée, 1946 - Lice

• Œuvres complètes, 1947 -

• Bourlinguer, 1948 - Planus

• Œuvres choisies, 1948

• La Banlieue de Paris, 1949

• Le Lotissement du ciel, 1949 - Sky: Memoirs

• Blais Cendras vous parlea..., 1952

• Le Brésil, 1952

• Emmène-moi au bout du monde!, 1953 - To the End of the World

• Trop c'est trop, 1957

• Du monde entier au cœur du monde, 1957

• A l'aventure, 1959

• Films sans images, 1959

• Œuvres complètes, 1960-1965 (8 vols.)

• Selected Writings of Blaise Cendrars. 1966 (ed. by Walter Albert)

• Inédits secrets, 1969

• Poésies complètes, 1967

• Œuvres complètes, 1968-1971 (15 vols.)

• Dites-nous Monsieur Blaise Cendrars, 1969

• Complete Postcards from the Americas: Poems of Road and Sea, 1976

• A Night in the Forest, 1985

• Paris ma ville, 1987 (illustrated by Fernand Léger)

• Modernities, 1992

• Complete Poems, 1992

• Christmas at the Four Corners of the Earth, 1994

• Voyager aved Blaise Cendrars, 1994

• Hollywood, 1995

• La vie et la mort di soldat inconnu, 1995

• L'eubage, 1995

• Correspondance 1934-1979, 1995 (Blaise Cendrars, Henry Miller)

• Shadow, 1995 (illustrated by Marcia Brown)

• La carissima: genèse et transformation, 1996 (ed. by Anna Maibach)

• Madame mon copain, 1997

LES CITATIONS DE BLAISE CENDRARS

«Rien n'est admissible ; sauf la vie, à condition de la réinventer chaque jour.»

«Pour être désespéré, il faut avoir vécu et aimer encore le monde.»

«Le seul fait d'exister est un véritable bonheur.»

«Ecrire, ce n'est pas vivre. C'est peut-être survivre.»

«L'univers est une digestion. Vivre est une action magique.»

- Emmène-moi au bout du monde

«Ecrire est une vue de l'esprit. C'est un travail ingrat qui mène à la solitude.»

- L'homme foudroyé

«Sans l'appui de l'égoïsme, l'animal humain ne se serait jamais développé. L'égoïsme est la liane après laquelle les hommes se sont hissés hors des marais croupissants pour sortir de la jungle.»

- Hors la loi!

«Je ne trempe pas ma plume dans un encrier mais dans la vie.»

«La sérénité ne peut être atteinte que par un esprit désespéré et, pour être désespéré, il faut avoir beaucoup vécu et aimer encore le monde.»

- Une nuit dans la forêt

«C'est dans ce que les hommes ont de plus commun qu'ils se différencient le plus.»

- Extrait d' Aujourd'hui

«La folie est le propre de l'homme.»

- Bourlinguer

«Quand on aime il faut partir.»

«Vivez, ah ! Vivez donc, et qu’importe la suite ! N’ayez pas de remords. Vous n’êtes pas Juge.»

- Bourlinguer

Etichette: amore, Cendrars, Henry Miller, musica, picaresco, poesia, traduzione, viaggiare, Whitman

...e tu?

...e tu?

Non sono riuscito a trovare in rete delle poesie di Cendrars tradotte in italiano.

C'e' ben poco di questo poeta/scrittore, che sembra essere dimenticato in Italia... e ovunque...

Dovro' trascrivere poesie da qualche libro pubblicato in Italia negli anni 60-70. Chi ne avesse, e' pregato di incollarmele qui

Merci.