~ Prosaico Henry Miller

MESSAGE

To paint is to love again.

It's only when we look with

eyes of love that we see

as the painter sees.

His is a love, moreover,

which is free of possessiveness.

What the painter sees

he is duty bound to share.

FromTo Paint is to Love Again

MESSAGGIO

Dipingere è di nuovo amare.

È solo quando guardiamo con

Occhi innamorati che vediamo

Ciò che vede il pittore.

Inoltre il suo è un amore

Libero da possessività.

Ciò che il pittore vede

Egli è costretto a condividere.

(trad. Daubmir)

IL TROPICO DEL CANCRO DI HENRY MILLER

Recensione di Fabrizio L. Lago e Andrea Famiglietti

Si può vivere senza amici, come si può vivere senza amore, o anche senza danaro, che tutti reputano un sine qua non.

A Parigi si può vivere - questo avevo scoperto - di dolore e di angoscia.

Amaro nutrimento, forse il migliore che ci sia per certe persone.

~Dal Tropico del Cancro

<< Questo non è un libro. E’ libello, calunnia, diffamazione. Ma non è un libro, nel senso usuale della parola. No, questo è un insulto prolungato, uno scaracchio in faccia all’Arte, un calcio alla Divinità, all’Uomo, al Destino, al Tempo, all’Amore, alla Bellezza… a quel che vi pare. Canterò per voi, forse stonando un po’, ma canterò. Canterò mentre crepate, danzerò sulla vostra sporca carogna…

<< Questo non è un libro. E’ libello, calunnia, diffamazione. Ma non è un libro, nel senso usuale della parola. No, questo è un insulto prolungato, uno scaracchio in faccia all’Arte, un calcio alla Divinità, all’Uomo, al Destino, al Tempo, all’Amore, alla Bellezza… a quel che vi pare. Canterò per voi, forse stonando un po’, ma canterò. Canterò mentre crepate, danzerò sulla vostra sporca carogna…Per cantare bisogna prima aprire la bocca. Ci vogliono un paio di polmoni, e qualche nozione di musica. Non occorre avere fisarmonica, o chitarra. Quel che conta è voler cantare. E dunque questo è canto. Io canto. >>

Inizia con queste premesse Tropico del Cancro, forse il più celebre romanzo di Henry Miller, vietato per quasi trent’anni in tutti i paesi anglosassoni (dal 1934, quando uscì presso una casa editrice parigina, al 1961, anno in cui ne fu liberalizzata la vendita negli Stati Uniti).

L’opera tratta della vita parigina dello scrittore americano, che scappa dalla sua patria alla ricerca di un nuova esistenza, fatta di quotidianità, di semplice sopravvivenza. Miller si ambienta perfettamente nella capitale francese, assieme ad altri connazionali diventa parte integrante del degrado urbano, della folta schiera di emarginati che riempiono i vicoli fatiscenti, gli alberghi in rovina, le stanze ad ore delle prostitute.

Il romanzo segue uno sviluppo caotico, non c’è una trama precisa, ma una serie di situazioni, fatte di cibo, sesso, conoscenze sporadiche che lo portano da un’avventura all’altra, quasi sempre per coincidenze. Miller assume un atteggiamento passivo verso gli eventi, non dà importanza a nulla che non sia il suo sostentamento. E’ come se si abbandoni alla vita ed al suo corso, volendone carpire solo ciò che gli serve a respirare, a godere, a non illudersi che esista un fine nobile o un ideale qualsiasi da perseguire. Miller vive la parentesi parigina da uomo scaltro, si lega a pochissime persone, forse a nessuno davvero, cerca di farsi offrire da bere o da mangiare da tutti: succhia la vita come un parassita la sua preda, assecondando l’egoistica asocialità disimpegnata, che permea la sua personalità.

Gli eventi si susseguono legati alle persone con cui lo scrittore passa le sue giornate, che fanno da ponti semantici alle sue riflessioni, ai suoi deliri. L’instabilità della sua vita non è casuale, spesso egli cita esplicitamente, in maniera critica, le abitudini della classe borghese parigina, a fronte della sua sregolatezza, del suo modo di soddisfarsi. Tale instabilità si fa più evidente sia nei suoi rapporti con le donne, considerate unicamente come oggetti sessuali, sia con i pochi amici, che si aggirano negli stessi quartieri frequentati da lui come meteore, che incrocia solo sporadicamente.

Miller si eleva realmente al di sopra di ogni morale e pregiudizio sociale. L’elemento eticamente degradato del vivere umano, lo attira inesorabilmente. L’autore vi si accosta, lo conosce in tutti i suoi risvolti e lo assimila, rendendolo parte integrante del suo caotico modus vivendi, senza alcun sentimento di campanilistica e provinciale vergogna.

Ciò che contraddistingue l’atteggiamento del protagonista nei confronti dell’esperienza parigina è la consapevole e naturale adattabilità ad ogni situazione umana, sociale ed economica; dimostra infatti, di saper fare veramente bene soltanto una cosa: vivere il presente. Ad un’attenta analisi delle scelte che Miller compie nell’arco di una giornata, emerge chiaramente questa attitudine, che, in fondo, è la chiave per il tipo di felicità della quale gode, come sostiene nelle prime righe del romanzo sostiene: << …Non ho soldi, né progetti, né speranze. Sono l’uomo più felice del mondo… >>.

L’unica costante del romanzo è la prevalenza dell’istinto. Contro qualunque razionalità di atteggiamenti, ricerca di sicurezze economiche, affettive, sociali, Miller prepone il vivere alla giornata, senza noiose prospettive di alcun genere.

Il quadro generale del romanzo si sviluppa dunque intorno ad un individualismo esistenziale, sterile, fine a se stesso, striato dalle grottesche storie delle persone con cui l’autore entra in contatto, per bisogno o fatalità. Si possono citare fra gli altri Boris, poeta e filosofo di strada dall’alcolico pessimismo rassegnato, “un profeta del tempo”, come lo definisce Miller; Van Norden, scarso pensatore, pretenzioso scrittore, molto più intento a procurarsi incontri sessuali di ogni genere, “un afficato, e basta”; Moldorf, “un ubriaco di parole…un baule pieno di cassetti e nei cassetti ci sono tante etichette…”. Le donne in Tropico del Cancro sono considerate solo come strumenti per ottenere piacere, uniche eccezioni sono Tania, la sola ad avere quella che si può chiamare una relazione con l’autore, e Ginette, la compagna di Fillmore, altro personaggio che trova un ruolo significativo nel romanzo, in diverse fasi.

Tania ha un passato con Miller precedente alla narrazione delle vicende di Tropico del Cancro, si lega di nuovo a lui a seguito di situazioni particolari, ne sconvolge le abitudini quotidiane, è causa di sofferenza, ma non cambia l’idea che lo scrittore ha dell’amore, citiamo alcuni passi significativi: << …spesso, mentre lei mi parlava, entusiasta, della Russia dell’amore e di tutte quelle stronzate, io mi mettevo a pensare alle cose più assurde, a fare il lustrascarpe, il guardiacessi…io immaginavo che il futuro, per quanto mediocre, sarebbe stato in un ambiente così…>>, o ancora: << …Ma il momento che la lasciavo mi si schiarivano le idee. Era un latro tipo di musica, non così sentimentale, ma buona lo stesso, che mi rallegrava le orecchie appena sorpassavo la porta girevole…>>.

Molte pagine del romanzo sono dedicate a Fillmore, l’amico che sembra stare più a cuore a Miller, forse l’unico a non avere nessuna ambizione artistica fra le sue conoscenze, anzi, uno che, approfittando del fatto di vivere in una stanza piena di quadri ereditati da un precedente inquilino pittore, cerca di fingersi artista per sedurre delle donne. L’attaccamento di Miller per Fillmore forse ha un significato anche alla luce di ciò. L’amico gli fa persino da mecenate e si preoccupa di spronarlo a produrre ogni giorno le pagine del suo romanzo, cosa che dopo poco infastidirà quest’ultimo. Ma il momento più intenso del rapporto con Fillmore si realizza con l’entrata in scena di Ginette, una donna che, dopo alterne vicende, tenta di incastrare l’amico in un matrimonio interessato. Forse in questa occasione si manifesta più intensamente il confronto fra Henry Miller e la vita, i sentimenti, i valori morali di un mondo in disfacimento, “divorato dal cancro del tempo”.

L’autore agisce in maniera ambigua, curando in parte il suo interesse e in parte quello di Fillmore, non chiarendo completamente i fatti nella conclusione.

Tropico del Cancro finisce con due brevi paragrafi sugli uomini e sul destino: il primo è un’affermazione assoluta del diritto a essere liberi degli esseri umani, il secondo una constatazione rassegnata dei limiti invalicabili dell’esistenza, metaforizzata dalla Senna che scorre davanti a lui: << …il suo corso è stabilito… >>. Ultimo e profondo contrasto di un libro, a nostro giudizio, magnifico, unico anche per il linguaggio originalissimo, antiletterario, testimonianza significativa della particolarissima migrazione intellettuale, anti-americana e anti-borghese, che si svolse nei tardi anni Venti, dagli States a Parigi.

DETTI DA HENRY

• Arriva un momento in cui realizzi che non ti sei semplicemente specializzato in qualcosa: qualcosa si è specializzato in te.

• Arriva un momento in cui realizzi che non ti sei semplicemente specializzato in qualcosa: qualcosa si è specializzato in te.• La storia del mondo è la storia di pochi privilegiati.

• La vita, com'è chiamata, è per molti di noi un lungo rinvio.

• A tenere insieme il mondo, come ho appreso da amare esperienze, sono i rapporti sessuali.

• Quel che non sta all'aperto è falso, derivato, cioè letteratura.

• Ogni uomo con la pancia piena di classici è un nemico della razza umana.

• È vero che nuoto in un perpetuo mare di sesso, ma le escursioni attuali sono abbastanza limitate.

• Il vero capo non ha bisogno di comandare - è pago nell'indicare la via.

• Il sesso è uno dei nove motivi per reincarnarsi... gli altri otto sono ininfluenti.

• Chiamiamo vizi quei divertimenti che non osiamo provare.

• Il primo impegno di uno scrittore è di liberare se stesso, diventare pulito del suo passato, della sua morte, diventare vivo. Una vittoria personale. Non c’è tempo per nessun’ altra cosa. Tutto il resto è letteratura - con un cattivo odore!

IL TEMPO DEGLI ASSASSINI

Un saggio di Henry Miller su Arthur Rimbaud

Henry Miller, come si sa, è un noto romanziere, famoso per alcuni suoi libri, uno tra tutti, Il tropico del cancro. A parte i romanzi, Miller si è dedicato anche ad opere di critica e di saggistica. Una in particolare si distingue per la capacità dell’autore di andare oltre la mera critica ai testi, nel tentativo, credo molto riuscito, di penetrare l’animo e la poesia del poeta che stava trattando. Il libro si chiama Il tempo degli assassini, un libro purtroppo difficilmente reperibile (forse è più facile trovarlo su qualche bancarella o in una biblioteca ben fornita,che in libreria) del 1986, edizioni Sugarco. E il grande poeta, di cui si parla in questo libro, è Arthur Rimbaud, l’enfant prodige, il diciassettenne che ha rivoluzionato la poesia contemporanea.

Rimbaud nasce a Charleville nel 1854, in un paesino non lontano da Parigi, un paese di campagna che, a distanza di oltre 150 anni, è rimasto intatto nelle sue origini contadine. Un paesino dove un piccolo ribelle come il nostro poeta sicuramente non poteva trovare posto. Rimbaud cresce irriverente, disgustato dal mondo contadino e dalla gente del suo paese. Due volte scappa di casa e per ben due volte è costretto a ritornarci. La sua esperienza poetica si consuma tra i sedici e i diciannove anni:in questi tre anni consegna ai posteri un patrimonio poetico rimasto intatto fino ad oggi e di cui si continua incessantemente a scrivere.

Miller parte da un suo ricordo che gli impediva di leggere Rimbaud perché questi era associato ad una persona che lui odiava. Ma una volta cominciato a leggere, Miller si appropria,si impadronisce del piccolo prodigio tentando di fare una comparazione tra le sue vicissitudini e quelle del poeta francese. Ne viene fuori un profilo giustamente apologetico che non indulge talvolta in alcune critiche, ma che riesce a descrivere mirabilmente l’essenza di Rimbaud:la sua genialità. Il suo essere diverso dagli altri, il suo desiderio di vivere fino alla fine ogni emozione, senza limiti.

Un genio tormentato da un’inquietudine profonda, da un’insoddisfazione tale che lo spinse, dopo i diciannove anni, a non scrivere più per tutta la sua vita, che lo portò a girovagare negli anfratti più sperduti della terra allora conosciuta, a scoprire nuove terre, a fare i lavori più impensabili. Un’inquietudine che lo portò a non curarsi della sua opera poetica, pubblicata interamente solo dopo la sua morte, grazie all’interessamento di Paul Verlaine,con il quale aveva avuto una relazione che stava rischiando di finire in tragedia, Paul Demeny e la sorella di Rimbaud, Isabelle.

Rimbaud morì sconosciuto come poeta all’età di 37 anni, dopo essere tornato dall’Africa per una cancrena che lo costrinse all’amputazione delle gambe e lo portò poi alla morte nell’ospedale della Conception a Marsiglia. Miller pone l’accento sulla genialità del poeta, sulla sua convinzione che i geni si trovano nei posti più impensabili:nei porti,nelle bettole,luridi,puzzolenti, desiderosi di consumare la loro vita nella pienezza. Desiderosi di vivere per se stessi. Probabilmente, a vederlo, Rimbaud sarebbe apparso agli occhi degli altri un semplice vagabondo, uno di questi anonimi scaricatori di porto,eppure un genio che aveva scritto a soli sedici anni “Le Bateau ivre”, certamente il suo capolavoro in versi, un viaggio in cui il poeta “mentre discendeva fiumi imperturbati, perse la guida dei suoi alatori”. Un viaggio al di sopra del bene e del male, alla scoperta dell’essenza della vita, alla ricerca del destino che lo aspettava. Tutto ciò concretizzato in immagini di una potenza evocativa eccezionale che permettono al lettore di partecipare a questa esperienza, a questo viaggio dove ogni contingenza scompare nel “poema del mare lattescente e infuso d’astri”.

Non mancano nel libro passi in cui Miller tenta di analizzare il profilo psicologico del poeta. Rimbaud che si allontana dalla famiglia e da sua madre come suo padre aveva fatto con lui. Rimbaud, ragazzino irriverente e ribelle, nel tentativo di difendersi dagli altri, per proteggere la sua profonda fragilità. Miller vede il suo vagabondaggio, di cui restano delle splendide poesie (Sensation, Ma bohème, Au Cabaret-Vert), come il mezzo per soddisfare il suo desiderio di conoscenza spinto fino ai limiti estremi,che lo portò a vivere ogni tipo di esperienza,da quella dell’oppio a quella omosessuale. Un desiderio di conoscenza che doveva portarlo allo “sregolamento dei sensi” di cui Rimbaud parla approfonditamente nella famosa “Lettera del Veggente”, un vero e proprio manifesto di una nuova poetica. Dalla lettura di questa lettera si può capire quanto Rimbaud fosse un precursore dei tempi,un’avanguardista che come tale era destinato a non essere compreso nella sua epoca. Un avanguardista che pagò sulla sua pelle il desiderio di conoscenza e il suo voler essere diverso a tutti i costi. Una diversità che lo portò ad inventare un linguaggio poetico nuovo,le cui lettere fossero formate dalle sue allucinazioni. Il rosso non è rosso,un albero non è verde:queste erano convenzioni che andavano smantellate e reinventate.

Oggi, se da Parigi, si sale sul treno per Charleville si attraversano delle campagne, le stesse che Rimbaud aveva visto dal treno quando si dirigeva a Parigi, desideroso di conoscere e di vivere esperienze nuove. È bello scoprire per chi si ferma a Charleville, nella piazza antistante la stazione, una statua dedicata al nostro poeta, una statua che lo ritrae ancora ragazzo. Ed è proprio da Charleville che Rimbaud è stato riconosciuto come un grande poeta, un genio ribelle, al quale la storia e l’arte hanno dato il giusto posto. Lui non ha voluto glorie in vita, ma la sua fama si perpetua nella poesia. Una tensione continua verso la chiave della vita. Una tensione che gli ha permesso di “possedere la verità in un’anima e in un corpo”.

(Gennaro De Falco)

...e ora qualcosa in inglese / and now for something in English:

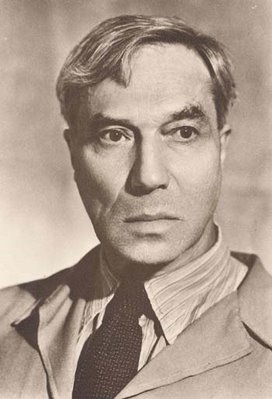

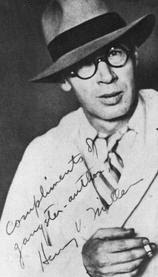

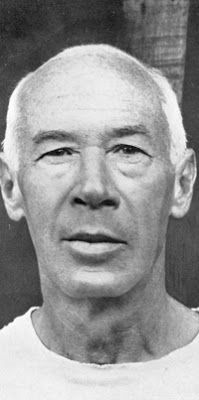

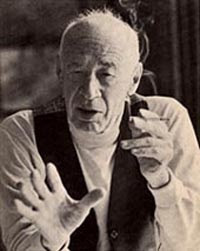

Henry Miller (1891-1980)

I believe that today more than ever a book should be sought after even if it has only one great page in it: we must search for fragments, splinters, toenails, anything that has ore in it, anything that is capable of resuscitating the body and soul. It may be that we are doomed, that there is no hope for us, any of us, but if that is so then let us set up a last agonizing, bloodcurdling howl, a screech of defiance, a war whoop! Away with lamentation! Away with elegies and dirges! Away with biographies and histories, and libraries and museums! Let the dead eat the dead. Let us living ones dance about the rim of the crater, a last expiring dance. But a dance!

~Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 1934

Henry Miller was born December 26, 1891 in New York, New York. During his first year of life, Miller's family moved to Brooklyn, where the whole of his childhood was spent. In 1909, Miller graduated from high school and entered City College of New York where he stayed for only two months. Not being able to bear the academic routine, Miller went to work at a variety of jobs. Everything from a cab driver to librarian. In 1917, Miller met and married the first of five wives, Beatrice Sylvas Wickens, with whom he has one child. Miller took a job with Western Union telegraph service in 1920 where his first endeavor into writing took place.

Miller's boss came to him one day with the idea that someone should write a book about messengers. He proposed something along the lines of "Horatio Alger," what Miller came up with was "Clipped Wings." This is a story of twelve messengers along the lines of Dostoevsky, rather than Horatio Alger. Miller wrote about "gentle souls, insulted and injured, who run amok or suffer violence; the stories are full of bitterness and horror, ending in murder or suicide, usually both". Miller realized that the work was a failure because he knew nothing of writing, but this endeavor spawned the urge to learn about writing.

Miller worked for the messenger service as a manager for four years until meeting his second wife, June Edith Smith Mansfield. June, a taxi driver, supported Miller so that he could pursue his artistic love and, at this point, life's dream. In 1928, June saved enough money for the two of them to travel to Europe, giving Miller a taste of what he considered civilized life. Problems with June persuaded Miller to leave for Paris in 1930, where he continued full time with his long and lucrative career as a writer of more than 36 creative and analytical works.

Miller's entrance into the writer's circle began with Tropic of Cancer, which still proves to be Miller's most famous work. Tropic of Cancer and Tropic of Capricorn chronicle Miller's lives and loves as an expatriate in Paris. They were both originally published in France by Jack Kahane at Obelisk Press in the mid-thirties. When the works were brought to the United States, they spawned a thirty year censorship debate that was eventually won by Miller. Tropic of Cancer and Tropic of Capricorn were published by Grove Press through the efforts of Barney Rosset. This event is still noted as the first "forced acceptance of banned books in the United States" (George Wickes, Henry Miller: Down and out in Paris, 1974).

Soon after the publishing of Tropic of Cancer and Tropic of Capricorn, Miller's other works to date were published in the United States. During this time it was said that "Miller became a legendary character, a kind of folk hero, the Paul Bunyan of literature, larger than life as exile, bohemian, and rebel, the great champion of freedom of expression and other lost causes". Miller's works became famous and were soon best sellers. Tropic of Cancer sold over two and a half million copies in the first two years of publication, thus earning Miller the comfort to live a life that he had not known as a beggar in the streets of Paris. Reflecting on those days, Miller would tell a story of the last time that he begged. A man dressed for the opera was walking in front of Miller, as he approached the man with the inevitable question: the man pushed Henry aside rudely and walked on without a word. Then with his back to Miller, he reached into his pockets and threw a handful of change in the mud filled gutter. "I was really degraded, humiliated, you know. But there I was down on my hands and knees, picking up the change and wiping the mud off. Right then and there I swore I'd never beg again and I didn't. I've known it all. Every humiliation, degradation, poverty, starvation".

Miller's days in Paris found him in the company of many characters. On his first visit to Europe he met Alfred Perles, a long friendship, documented in Miller's book Quiet Days in Clichy, ensued. Along with Perles, Miller had another close male friend called Michael Fraenkel, with whom he co-authored the book Hamlet. Hamlet is based on the letters of the two men. They made a pack with each other to continue writing letters on a variety of subjects, beginning with Shakespeare's Hamlet. The agreement was based on letters that could not end until, together, they had completed one thousand pages. Both men were avid arguers and had no problem continuing their individual diatribes. Miller's final letter was over one hundred pages long. "Miller found the letter a congenial form, a written monologue, running on about the weather, ideas, books, recent experiences, all loosely linked by the amusing personality of the writer" (Wickes 1974).

While in Paris, Miller also befriended a woman who was to be a long time lover and occasional benefactor, Anais Nin. Their friendship is ironically documented by Nin rather than Miller. Her diaries which fill a multitude of volumes document social engagements, their love affair and a love affair with Miller's wife, June. These stories were made famous in the 1992 feature film, Henry and June. Although Nin was married, they spent several years as lovers and critics of each others work while Miller was in Paris.

Miller left Paris in 1939 after the publication of Tropic of Capricorn. A life long friend whom Miller met in Paris, Lawrence Durell, had many times invited Miller to come to Greece. Now that Miller was out from under the weight of Tropic of Capricorn, he had the freedom to take Durell up on the offer. Miller's six months in Greece were filled with constant celebration until the outbreak of World War II, which prompted his return to the United States. While in Greece Miller wrote what many critics believe to be his finest work of "literature," The Colossus of Maroussi. This is basically a travel book with a bit more. The Colossus of Maroussi conveys a metaphysical insight into the place which Miller considers a "holy land." What Miller tried to achieve with the book was "not archaeology or history, but a feeling of kinship with the men of the past" (Wickes 1974).

Upon Miller's return to the United States, he decided to travel the country which was the impetus of another travel book, The Air-Conditioned Nightmare. "Why is it that in America the great works of art are all Nature's doing?" Miller believed that the majority of people in the United States were all dead, "all but the Negroes, Indians and an occasional nonconformist. The American way of life has created a spiritual and cultural wasteland." While Miller was traveling the United States he happened upon Big Sur where he settled and lived from 1944 to 1963.

When Miller moved to Big Sur he helped establish the area as an artists colony with himself being the "leading prophet," aside from Robinson Jeffers, who had been in the area since 1914. At this time Miller had not quite achieved the fame that would eventually ensue after the publication of Tropic of Cancer, but a great many people made pilgrimages to visit the great "underground" writer that had been banned in the United States. "Pilgrims came from all parts of the country and abroad, so many that eventually he had to leave. It is characteristic of America and this day of public images that Miller should be identified as the monkish Sage of Big Sur" (Wickes 1974).

Now with an audience, Miller's writing went through a transformation. Miller became more "literary," a word and concept that disgusted him. His thoughts became more spiritual yet, cohesive with form and analysis. Theme began to surface clearly. While in the past his writing had been a pure, stream of conscious type documentation, his writing became clear and the want for an audience dissipated. After so many years of want, the lust for fame left him.

While living in Big Sur, Miller married two more of his eventual five wives, Janina Martha Lepska, with who he had two children, and in 1953, Eve McClure. With his two children, Tony and Valentine, Miller lived on Partington Ridge, also referred to as Anderson's Point. The house was on a plateau two thousand feet above the Pacific Ocean. "About fifty feet from the house, the land simply ended, and it was an abrupt decent to the sea far below." At this place in Miller's life he finished the work that immortalized Big Sur in the world of literature, Big Sur and the Oranges of Hieronymus Bosch. Big Sur and the Oranges of Hieronymus Bosch was Miller's Walden. Big Sur conjured up the concept of a utopia for Miller, as Walden had done for Thoreau.

Finally in 1960 it became too much for Miller and his present wife, Eve McClure. The constant visitors and imposing house guests. Their world had taken on a busyness that caused Miller to often stop and think "Where was I?" After traveling around Europe for a year, Miller retired himself to Pacific Palisades in Southern California. Here he left the practice of writing daily and substituted it with painting daily. He still wrote and published occasionally, but writing was no longer the driving force in Miller's life.

The last twenty years of Miller's life, spent in Pacific Palisades, were humbling ones. His body slowly deteriorated, yet his wit and artistic capabilities stayed in tact. Miller spent much of his time reflecting on his turbulent life with interviewers and close friends. When often questioned about writing he has said, "It's a curse. Yes, it's a flame. It owns you. It has possession over you. You are not the master of yourself. You are consumed by this thing. And the books you write. They're not you. They're not me sitting here, this Henry Miller. They belong to someone else. It's terrible. You can never rest. People used to envy me my inspiration. I hate inspiration. It takes you over completely. I could never wait until it passed and I got rid of it".

Miller's life ended on June 7, 1980 in his Pacific Palisades home. He was with his caregiver Bill Pickerill, who had lived with Miller for several years. The clearest end for Miller's own life come from his own words, written in The Smile at the Foot of the Ladder: Perhaps I have not limned his portrait too clearly. But if he exists, if only for the reason that I have imagined him to be. He came from the blue and returns to the blue. He has not perished, he is not lost. Neither will he be forgotten.

* * *

HENRY SAID...

Actors die so loud.

An artist is always alone - if he is an artist. No, what the artist needs is loneliness.

Any genuine philosophy leads to action and from action back again to wonder, to the enduring fact of mystery.

Art is only a means to life, to the life more abundant. It is not in itself the life more abundant. It merely points the way, something which is overlooked not only by the public, but very often by the artist himself. In becoming an end it defeats itself.

Chaos is the score upon which reality is written.

Confusion is a word we have invented for an order which is not understood.

Develop an interest in life as you see it; the people, things, literature, music - the world is so rich, simply throbbing with rich treasures, beautiful souls and interesting people. Forget yourself.

Develop interest in life as you see it; in people, things, literature, music - the world is so rich, simply throbbing with rich treasures, beautiful souls and interesting people. Forget yourself.

Every man has his own destiny: the only imperative is to follow it, to accept it, no matter where it leads him.

Every man with a bellyful of the classics is an enemy to the human race.

Every moment is a golden one for him who has the vision to recognize it as such.

I have never been able to look upon America as young and vital but rather as prematurely old, as a fruit which rotted before it had a chance to ripen.

I have no money, no resources, no hopes. I am the happiest man alive.

I see America spreading disaster. I see America as a black curse upon the world. I see a long night settling in and that mushroom which has poisoned the world withering at the roots.

If men cease to believe that they will one day become gods then they will surely become worms.

If there is to be any peace it will come through being, not having.

If we are always arriving and departing, it is also true that we are eternally anchored. One's destination is never a place but rather a new way of looking at things.

Imagination is the voice of daring. If there is anything Godlike about God it is that. He dared to imagine everything.

In expanding the field of knowledge we but increase the horizon of ignorance.

In this age, which believes that there is a short cut to everything, the greatest lesson to be learned is that the most difficult way is, in the long run, the easiest.

It isn't the oceans which cut us off from the world - it's the American way of looking at things.

Life has to be given a meaning because of the obvious fact that it has no meaning.

Life is 440 horsepower in a 2-cylinder engine.

Life is constantly providing us with new funds, new resources, even when we are reduced to immobility. In life's ledger there is no such thing as frozen assets.

Life, as it is called, is for most of us one long postponement.

Madness is tonic and invigorating. It makes the sane more sane. The only ones who are unable to profit by it are the insane.

Moralities, ethics, laws, customs, beliefs, doctrines - these are of trifling import. All that matters is that the miraculous become the norm.

Music is a beautiful opiate, if you don't take it too seriously.

Nine-tenths of our sickness can be prevented by right thinking plus right hygiene - nine-tenths of it!

No man is great enough or wise enough for any of us to surrender our destiny to. The only way in which anyone can lead us is to restore to us the belief in our own guidance.

No matter how vast, how total, the failure of man here on earth, the work of man will be resumed elsewhere. War leaders talk of resuming operations on this front and that, but man's front embraces the whole universe.

Obscenity is a cleansing process, whereas pornography only adds to the murk.

One has to be a lowbrow, a bit of a murderer, to be a politician, ready and willing to see people sacrificed, slaughtered, for the sake of an idea, whether a good one or a bad one.

One of the reasons why so few of us ever act, instead of react, is because we are continually stifling our deepest impulses.

One's destination is never a place but rather a new way of looking at things.

Our own physical body possesses a wisdom which we who inhabit the body lack. We give it orders which make no sense.

Plots and character don't make life. Life is here and now, anytime you say the word, anytime you let her rip.

Sex is one of the nine reasons for reincarnation... the other eight are unimportant.

The aim of life is to live, and to live means to be aware, joyously, drunkenly, serenely, divinely aware.

The concert is a polite form of self induced torture.

The great work must inevitably be obscure, except to the very few, to those who like the author himself are initiated into the mysteries. Communication then is secondary: it is perpetuation which is important. For this only one good reader is necessary.

The legal system is often a mystery, and we, its priests, preside over rituals baffling to everyday citizens.

The man who is forever disturbed about the condition of humanity either has no problems of his own or has refused to face them.

The one thing we can never get enough of is love. And the one thing we never give enough is love.

The only thing we never get enough of is love; and the only thing we never give enough of is love.

The ordinary man is involved in action, the hero acts. An immense difference.

The real leader has no need to lead - he is content to point the way.

The waking mind is the least serviceable in the arts.

The world is not to be put in order; the world is order, incarnate. It is for us to harmonize with this order.

There is no salvation in becoming adapted to a world which is crazy.

There is nothing strange about fear: no matter in what guise it presents itself it is something with which we are all so familiar that when a man appears who is without it we are at once enslaved by him.

True strength lies in submission which permits one to dedicate his life, through devotion, to something beyond himself.

Until we accept the fact that life itself is founded in mystery, we shall learn nothing.

We do not talk - we bludgeon one another with facts and theories gleaned from cursory readings of newspapers, magazines and digests.

We have two American flags always: one for the rich and one for the poor. When the rich fly it means that things are under control; when the poor fly it means danger, revolution, anarchy.

We live at the edge of the miraculous.

We live in the mind, in ideas, in fragments. We no longer drink in the wild outer music of the streets - we remember only.

We should read to give our souls a chance to luxuriate.

What distinguishes the majority of men from the few is their ability to act according to their beliefs.

What holds the world together, as I have learned from bitter experience, is sexual intercourse.

Whatever I do is done out of sheer joy; I drop my fruits like a ripe tree. What the general reader or the critic makes of them is not my concern.

Whatever needs to be maintained through force is doomed.

Whatever there be of progress in life comes not through adaptation but through daring, through obeying the blind urge.

Whatever there be of progress in life comes not through adaptation but through daring.

When one is trying to do something beyond his known powers it is useless to seek the approval of friends. Friends are at their best in moments of defeat.

From

From PLEXUS

by Henry Miller

To write, I meditated, must be an act devoid of will. The word, like the deep ocean current, has to float to the surface of its own impulse. A child has no need to write, he is innocent. A man writes to throw off the poison which has accumulated because of his false way of life. He is trying to recapture his innocence, yet all he succeeds in doing (by writing) is to inoculate the world with a virus of his disillusionment. No man would set a word down on paper if he had the courage to live out what he believed in. His inspiration is deflected at the source. If it is a world of truth, beauty and magic that he desires to create, why does he put millions of words between himself and the reality of that world? Why does he defer action - unless it be that, like other men, what he really desires is power, fame, success. 'Books are human actions in death,' said Balzac. Yet, having perceived the truth, he deliberately surrendered the angel to the demon which possessed him.

A writer woos his public just as ignominiously as a politician or any other mountebank; he loves to finger the great pulse, to prescribe like a physician, to win a place for himself, to be recognized as a force, to receive the full cup of adulation, even if it be deferred a thousand years. He doesn't want a new world, which might be established immediately, because be knows it would never suit him. He wants an impossible world in which he is the uncrowned puppet-ruler dominated by forces utterly beyond his control. He is content to rule insidiously - in the fictive world of symbols - because the very thought of contact with rude and brutal realities frightens him. True, he has a greater grasp of reality than other men, but he makes no effort to impose that higher reality on the world by force of example. He is satisfied just to preach, to drag along in the wake of disaster and catastrophes, a death-croaking prophet always without honour, always stoned, always shunned by those who, however unsuited for their talks, are ready and willing to assume responsibility for the affairs of the world. The truly great writer does not want to write: he wants the world to be a place in which he can live the life of the imagination The first quivering word he puts to paper is the word of the wounded angel: pain. The process of putting down words is equivalent to giving oneself a narcotic. Observing the growth of a book under his hands, the author swells with delusions of grandeur. 'I too am a conqueror - perhaps the greatest conqueror of all! My day is coming. I will enslave the world - by the magic of words...' Et cetera ad nauseam.

The little phrase - Why don't you try to write? - involved me, as it had from the very beginning, in a hopeless bog of confusion. I wanted to enchant but not to enslave; I wanted a greater, richer life, but not at the expense of others; I wanted to free the imagination of all men at once because without the support of the whole world, without a world imaginatively unified, the freedom of the imagination becomes a vice. I had no respect for writing per se any more than I had for God per se. Nobody, no principle, no idea, has validity in itself. What is valid is only that much - of anything, God included - which is realized by all men in common. People are always worried about the fate of the genius. I never worried about the genius: genius takes care of the genius in a man. My concern was always for the nobody, the man who is lost in the shuffle, the man who is so common, so ordinary, that his presence is not even noticed. One genius does not inspire another. All geniuses are leeches, so to speak. They feed from the same source - the blood of life. The most important thing for the genius is to make himself useless, to be absorbed in the common stream, to become a fish again and not a freak of nature. The only benefit, I reflected, which the act of writing could offer me was to remove the differences which separated me from my fellow man. I definitely did not want to become the artist, in the sense of becoming something strange, something apart and out of the current of life.

The best thing about writing is not the actual labor of putting word against word, brick upon brick, but the preliminaries, the spadework, which is done in silence, under any circumstances, in dream as well as in the waking state. In short; the period of gestation. No man ever puts down what he intended to say: The original creation, which is taking place all the time, whether one writes or doesn't write, belongs to the primal flux: it has no dimensions, no form, no time element. In this preliminary state, which is creation and not birth, what disappears suffers no destruction: something which was already there, something imperishable, like memory, or matter, or God, is summoned and in it one flings himself like a twig into a torrent. Words, sentences, ideas, no matter how subtle or ingenious, the maddest flights of poetry, the most profound dreams, the most hallucinating visions, are but crude hieroglyphs chiseled in pain and sorrow to commemorate an event which is untransmissable. In an intelligently ordered world there would be no need to make the unreasonable attempt of putting such miraculous happenings down. Indeed, it would make no sense, for if men only stopped to realize it, who would be content with the counterfeit when the real is at everyone's beck and call? Who would want to switch in and listen to Beethoven, for example, when he might himself experience the ecstatic harmonies which Beethoven so desperately strove to register. A great work of art, if it accomplishes anything, serves to remind us, or let us say to set us dreaming, of all that is fluid and intangible. Which is to say, the universe. It cannot be understood; It can only be accepted or rejected. If accepted we are revitalized: if rejected we are diminished. Whatever it purports to be it is not: It is always something more for which the last word will never be said. It is all that we put into it out of hunger for that which we deny every day of our lives. If we accepted ourselves as completely, the work of art, in fact the whole world of art would die of malnutrition. Every man Jack of us moves without feet at least at least a few hours a day, when his eyes are closed and his body prone. The art of dreaming when wide awake will be in the power of every man one day. Long before that books will cease to exist, for when men are wide awake and dreaming their powers of communication (with one another and with the spirit that moves all men) will be so enhanced as to make writing seem like the harsh and raucous squawks of an idiot.

I think and know all this, lying in the dark memory of a summer's day, without having mastered, or even halfheartedly attempted to master, the art of the crude hieroglyph. Before ever I begin I am disgusted with the efforts of the acknowledged masters. Without the ability or the knowledge to make so much as a portal in the facade of the ground edifice, I criticize and lament the architecture itself; If I were only a tiny brick in the vast cathedral of this antiquated facade I would be infinitely happier; I would have life, the life of the whole structure, even as an infinitesimal part of it. But I am outside, a barbarian who cannot make even a crude sketch, let alone a plan of the edifice he dreams of inhabiting. I dream a new blazingly magnificent world which collapses as soon as the light is turned on. A world that vanishes but does not die, for I have only to become still again and stare wide-eyed into the darkness and it reappears.

...There is then a world in me which is utterly unlike any world I know of. I do not think it is my exclusive property - it is only the angle of my vision which is exclusive, in that it is unique. If I talk the language of my unique vision nobody understands: the most colossal edifice may be reared and yet remain invisible. The thought of that haunts me. What good will it do to make an invisible temple?

Etichette: Cendrars, Henry Miller, picaresco, Rimbaud

...e tu?

...e tu?